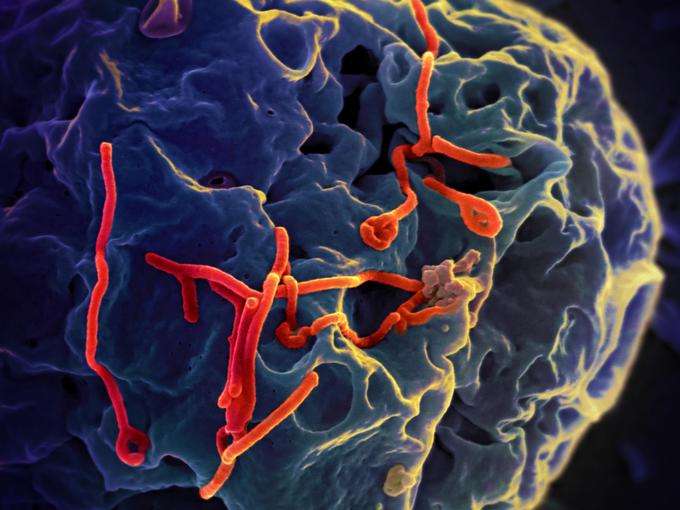

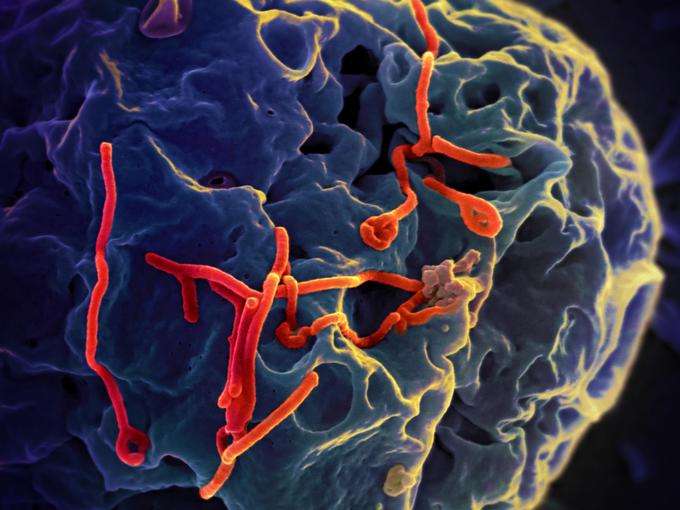

This isn’t the first Ebola outbreak the world has seen. First identified in 1976, Ebola has emerged sporadically over the last few decades, most often occurring in remote villages in Africa. But the current outbreak, the largest on record, begs the question: What does this Ebola crisis reveal about global health?

For one, it affirms that diseases easily cross borders. In a

Boston Globe article in early October , Dr. Sandro Galea, chairman of the epidemiology department at Columbia University, called Ebola a “wake-up call to the world.” Society has become more interconnected and dramatically more urban and “those shifting demographics have removed any pretense we may have once had that problems over there are problems over there,” said Galea.

The outbreak also opens up discussion about why a vaccine doesn’t exist. “Ebola emerged nearly four decades ago,” said Dr. Margaret Chan, director-general of the World Health Organization (WHO), in an

address to the regional committee for Africa on Nov. 3. “Why are clinicians still empty-handed, with no vaccines and no cure? Because Ebola has historically been confined to poor African nations, and a profit-driven [pharmaceutical] industry doesn’t invest in products for markets that cannot pay.”

How quickly have Ebola cases stacked up?

The current outbreak includes 13,567 cases as of Oct. 31, according to the

WHO . The Ebola outbreak has been most intense in West Africa: More than 13,000 people in Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Mali, Nigeria and Senegal have been afflicted with the disease since March. More than 4,900 people have died.

The WHO declared that Ebola outbreaks in

Nigeria and Senegal were over on Oct. 17 and Oct. 19, respectively.

There have been nearly 20 cases treated in Europe and the

United States , many of which were health care workers who contracted Ebola in West Africa and were transported home to be treated. Most recently, Dr. Craig Spencer, a Doctors Without Borders volunteer in Guinea, returned to New York City and tested positive for Ebola following a symptom-free week. He’s currently in stable condition at Bellevue Hospital.

Hospitals respond: NYC vs. Dallas

Earlier cases included one on Sept. 30, the first Ebola case diagnosed in the United States. Thomas Eric Duncan, a Liberian man who traveled to Dallas, Texas, died on Oct. 8. On Oct. 11, a second U.S. case was diagnosed:

Nina Pham , a nurse who cared for the patient. Days later, a second nurse, Amber Joy Vinson, was also diagnosed with Ebola. Both health care workers were released virus-free in late October.

Questions about safety protocols and travel clearance (Vinson was cleared by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to fly the day before her diagnosis) spurred

national debate .

But unlike Dallas, New York City handled its Ebola case differently, partly because officials had more time to prepare. On Oct. 21, more than 5,000 health care workers attended a training session in NYC, where they learned protocols, such as the proper way to use protective equipment. This training followed

updated guidelines from the CDC.

Politics of Ebola: Government vs. science

As U.S. officials ramped up efforts, they hit several walls.

New York Governor Andrew Cuomo and New Jersey Governor Chris Christie announced

mandatory 21-day quarantines for medical workers returning from West Africa. Additionally, five U.S. airports began screening travelers from West Africa: Kennedy International, Washington Dulles International, O’Hare International, Hartsfield-Jackson International and Newark Liberty International.

But when Maine nurse Kaci Hickox— who was initially quarantined at Newark Liberty International airport after her return from West Africa— took a neighborhood bike ride, openly defying a quarantine order, she ignited a

legal and ethical debate .

The medical community fired back: “The best way to protect us is to stop the epidemic in Africa, and we need those health care workers, so we don’t want to put them in a position where it makes it very, very uncomfortable for them to even volunteer to go,” said Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, on a Sunday morning political talk show.

Once isolated Ebola cases began appearing, the United States fell to the risk of “misguided self-interest,” said Lawrence Gostin, a Georgetown University professor who specializes in public health law. In his

Health Affairs blog , Gostin referenced travel bans and quarantines, saying, “We’re transferring our gaze from the real crisis and headed on an insular journey.”

Drug development to prevent or treat Ebola

There are more than a dozen Ebola drugs in development, but while none have been formally approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), some have been approved for emergency use. ZMapp, which is made in tobacco plants, was used on two patients in the United States, but there were no more doses available as of early October.

Efforts to find a vaccine have been

fast-tracked in recent months. WHO officials reported on Oct. 24 that they hope to begin vaccine trials as early as December of this year. Human testing of at least

five other vaccines could begin in early 2015, WHO officials said.

The WHO also reported in mid-October that the number of

new Ebola cases could reach 10,000 per week by December.

“Ebola is a game changer,” said Gostin. “All the things we thought about in terms of research priorities and development of drugs and vaccines need to be rethought.”

This isn’t the first Ebola outbreak the world has seen. First identified in 1976, Ebola has emerged sporadically over the last few decades, most often occurring in remote villages in Africa. But the current outbreak, the largest on record, begs the question: What does this Ebola crisis reveal about global health?

This isn’t the first Ebola outbreak the world has seen. First identified in 1976, Ebola has emerged sporadically over the last few decades, most often occurring in remote villages in Africa. But the current outbreak, the largest on record, begs the question: What does this Ebola crisis reveal about global health?