American official: US in Ebola fight for long haul

The United States will help fight Ebola over "the long haul," the American ambassador to the United Nations said on a trip to the West African countries hit by the outbreak.

Samantha Power will be in Sierra Leone on Monday. She met Sunday with religious leaders in Guinea, where the Ebola outbreak was first identified in March.

"We are in this with you for the long haul," she said. The outbreak has killed nearly 5,000 people, the vast majority of them in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. "We have got to overcome the fear and the stigma that are associated with Ebola."

Many people hide in their homes rather than seek medical care because of fears that an Ebola diagnosis is an automatic death sentence and the social stigma attached to the disease, further fueling its spread. So far, more than 10,000 people are believed to have been infected.

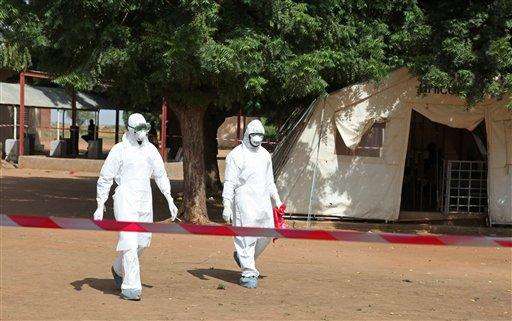

There is no licensed treatment or vaccine for Ebola, so separating the sick from the healthy is the only way to stop Ebola's transmission. But that job has been made difficult because there aren't enough beds in Ebola treatment centers or enough ambulances to bring people there.

France sent 30 members of a government disaster-preparedness corps to Guinea this weekend to offer training on how to transport people who have Ebola-like symptoms and how to track down people with whom they've had contact.

Health authorities are meant to rigorously track down everyone who has had contact with the sick and monitor or even isolate them during the disease's incubation period, which can last up to 21 days. However, the disease spread for so long before it was identified in West Africa that tracing contacts has been difficult, if not impossible, in the worst-hit countries.

Other countries with one or only a handful of cases have been more successful. Mali, which announced its first Ebola case last week in a 2-year-old who traveled on public transportation from Guinea, was monitoring 47 people on Monday who had contact with the toddler.

Markatie Daou, a health ministry spokesman, said the little girl, who has since died, remains the only person in Mali who has tested positive for the disease. But the World Health Organization has warned that many people may have had "high-risk" contact with the girl, who was bleeding from her nose during the journey.

Meanwhile, 10 people who had contact with a Spanish nursing assistant who survived Ebola were released Monday from a Madrid hospital after spending 21 days under observation and showing no symptoms, a hospital official said. She spoke on condition of anonymity in keeping with hospital policy.

___

Associated Press writers Baba Ahmed in Bamako, Mali, Boubacar Diallo in Conakry, Guinea, and Ciaran Giles and Alan Clendenning in Madrid contributed to this report.