A common antidepressant can dramatically halt growth of Alzheimer’s plaque.

A common antidepressant can dramatically halt growth of Alzheimer’s plaque.

A team from Missouri and Pennsylvania report today in Science Translational Medicine this reduction occurs in both humans and mice. It gives the drug, the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) citalopram, a possible future role as a prophylactic—the first in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), if bigger studies are supportive.

“I was surprised the effect on plaque growth and prevention in transgenic mice was so large,” first author Yvette Sheline told Bioscience Technology. Sheline is director of the University of Pennsylvania Center for Neuromodulation in Depression and Stress. “We are hopeful that we can proceed in a systematic way to develop a preventive treatment for AD.”

“I found Yvette’s paper quite interesting,” Stanford University AD researcher Laurence Steinman said via email. Steinman was not involved with the study.

“I think this is an important paper,” Howard Fillit echoed in an interview with Bioscience Technology. Fillit is chief scientific officer of the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation. He offered a corollary, however, given that a small February JAMA study, while “exciting,” did find citalopram may cause cognitive problems after AD onset: “The biology of SSRIs is really interesting. But we have cured mice of Alzheimer’s 400 times. I hope this leads to a Phase 2b or 3 study, to look at whether citalopram and other SSRIs can be disease-modifying agents for AD.”

“Impresssive” 78 Percent Plaque Reduction

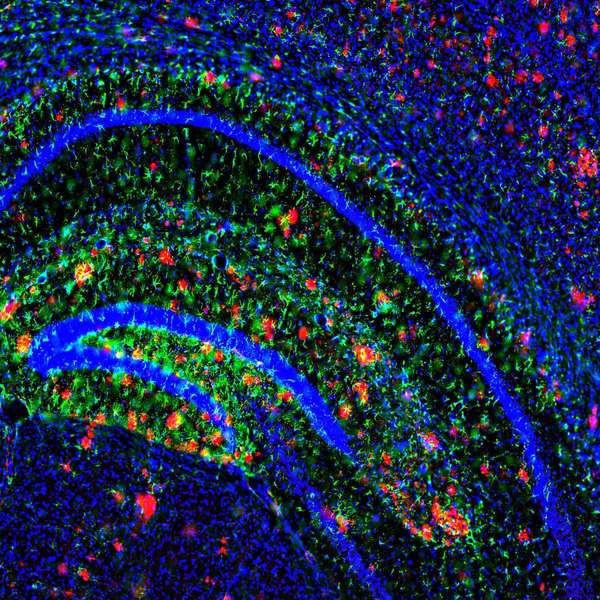

The group used serial two-photon imaging on mouse models of AD for 28 days. They showed that, in the rodents, citalopram halted growth of the primary component in AD plaque, amyloid beta (Ab), and “significantly reduced the appearance of new plaques” in brain interstitial fluid by 78 percent, according to the report. The group previously showed SSRIs can lower production of plaque in rodent brains—pre-Alzheimer’s--by 25 percent. This study focused on citalopram (Celexa/Cipramil), and established the effect as dose-dependent.

The group also studied healthy human volunteers for a shorter period. A pill containing citalopram or placebo was given to 23 healthy, non-depressed people aged 18 to 50 at midnight. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) collection started the next morning, and over a 24-hour period. “Citalopram’s effects on Ab production and Ab concentrations in CSF were measured prospectively using stable isotope labeling kinetics, with CSF sampling during acute dosing of citalopram,” the report noted. “Ab production in CSF was slowed by 37 percent in the citalopram group compared to placebo. This change was associated with a 38 percent decrease in total CSF Ab concentrations in the drug-treated group. The ability to safely decrease Ab concentrations is potentially important as a preventive strategy for AD.”

The maximum effective dose of citalopram causing a reduction in brain Ab concentrations and plaques in mice (10 mg/kg) was comparable to a dose of citalopram (50 mg/day) often given to humans as an antidepressant, and similar to the dose used in this study: 60 mg.

In earlier work, Sheline and this study’s senior author, University of Washington neurologist John Cirrito, showed “SSRI exposure within the five years before amyloid PET scan was associated with lower amyloid binding as determined by PIB-PET imaging,” according to the report. “A recently discovered protective mutation in APP [amyloid precursor protein] (A673T) has approximately the same magnitude of Ab-lowering effect as the citalopram effect in the current study, strengthening the argument for SSRIs as a potential AD prevention strategy.”

In earlier work, Sheline and this study’s senior author, University of Washington neurologist John Cirrito, showed “SSRI exposure within the five years before amyloid PET scan was associated with lower amyloid binding as determined by PIB-PET imaging,” according to the report. “A recently discovered protective mutation in APP [amyloid precursor protein] (A673T) has approximately the same magnitude of Ab-lowering effect as the citalopram effect in the current study, strengthening the argument for SSRIs as a potential AD prevention strategy.”

A potential problem, Steinman says: “If plaque burden reflects severity of AD, and it's a big 'if,’ then a 78 percent reduction in plaque burden is impressive. But there are many with dementia without plaques at all.”

Fillit agrees plaque could be a “bystander. AD is complicated. There are all kinds of competing morbidities at work.” But certainly, he said, depression is a key AD risk factor, one of many things that make SSRIs interesting candidates for study.

SSRIs May Work Differently Pre/Post Alzheimer’s

Furthermore, it may matter the above-mentioned JAMA study found citalopram may impede cognition after AD onset—while this study found it affected plaque before, he said. Cirrito, speaking by email, agreed. “The data we have so far suggests that SSRIs prevent growth of plaques and reduce formation of new plaques, but does not shrink plaques. If SSRIs ever become a therapy, it would likely need to be very early in disease or before symptoms even start. I suspect this is likely true for most drugs currently being developed to target Ab as a therapy.”

Regardless, the fact that the JAMA study found that citalopram reduced agitation is “very exciting,” said Fillit. “Some 50 percent of patients with clinical AD have behavioral disorders disabling for them, and causing severe caregiver distress. We have no effective drugs for it.”

One question many would like answered: mechanism of action. The pathway the drug uses to initiate plaque-reduction may differ from the pathway it uses for mood-boosting. SSRI depression therapy takes weeks to kick in. The anti-plaque effect occurred in hours. On the other hand, a more delayed benefit of SSRIs can be neuron protection and generation, Fillit noted.

Cirrito found the February JAMA paper “certainly interesting.” It “likely has sufficient power to make conclusions about improvement in agitation (their primary endpoint). Cognition/dementia is usually more variable and difficult to detect changes, however, which means you need a much larger number of individuals. The JAMA paper was short (nine weeks) and only in ~90 individuals per group, which means their cognition result is interesting, but likely far from conclusive. A true test of the SSRI hypothesis on cognition will need much larger numbers and longer treatment.”

Moving Forward

The team is already moving on. “The next step we will take—momentarily—is to enroll older cognitively normal volunteers to have their CSF tested for amyloid concentration before, and after, taking an SSRI or placebo for two weeks,” Sheline said via email. This will let them “determine if the drug effect is sustained. If that trial is successful, then we will plan a prevention trial where we use an SSRI to treat cognitively normal elderly at risk for AD. We hope to show that giving an SSRI for several years prevents brain plaque growth as determined by PET scan.”

She added: “I am not surprised by the JAMA findings. That is a completely different use of the drug--in people who already have known AD. We do not expect any efficacy in treating dementia. We will only be using SSRIs in cognitively normal people. We are hoping to show (eventually) that these drugs slow the course of pre-clinical dementia, e.g., when cognitively normal people have increased amyloid burden, but before they have dementia signs. There is about a 15-year time period during which amyloid burden increases, before the beginning of dementia. For their amyloid-lowering properties, SSRI drugs work through specific serotonin receptor subtypes to impact extracellular kinase (ERK), which in turn up-regulates alpha secretase. This is a different mechanism from their anti-depressant effect.”