On the Trail of Ancient Wines and Beers

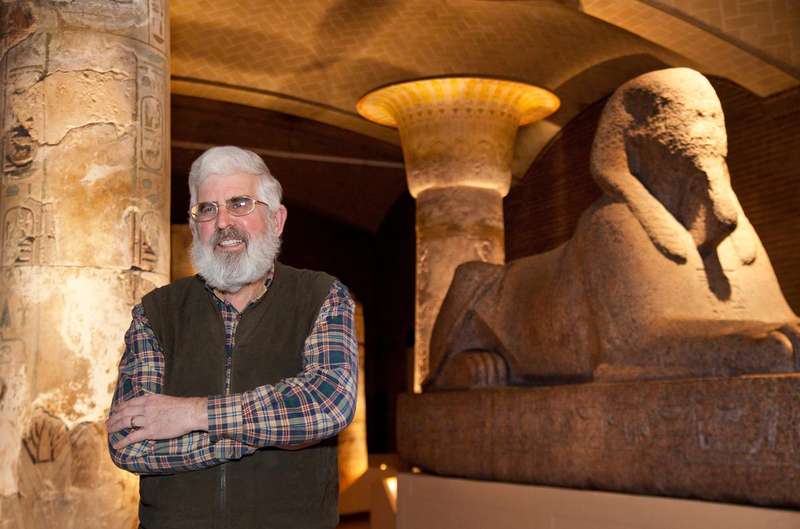

Patrick McGovern has successfully combined two widely varying facets of his life into a career that sets him apart from most anyone else. He is an archaeologist devoted to studying ancient artifacts and trying to piece together their role in advancing civilization. But his specialty is focused on the origins and expansion of the fermentable beverages of early civilizations, which suits him perfectly as the director of the Biomolecular Archaeology Project at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia.

Patrick McGovern has successfully combined two widely varying facets of his life into a career that sets him apart from most anyone else. He is an archaeologist devoted to studying ancient artifacts and trying to piece together their role in advancing civilization. But his specialty is focused on the origins and expansion of the fermentable beverages of early civilizations, which suits him perfectly as the director of the Biomolecular Archaeology Project at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia.

McGovern is a doctor of drinkology, a fermentation archaeologist.

He believes that human’s fondness for alcoholic beverages, and there are signs of it everywhere past and present, has had a profound impact on making us what we are and civilization what it is.

“Wherever we look in the ancient or modern world, humans have shown a remarkable ingenuity in discovering how to make fermented beverages and incorporating them into their cultures,” McGovern says. “For example, African cultures, where our species began, are awash in sorghum and millet beers, honey mead and banana and palm wines.”

McGovern is a leading expert on ancient fermented beverages. He has found incredible value in the residue dried in the bottom of ancient vessels unearthed at archaeological sites, residue that had been largely ignored by most archaeologists.

He scrapes the residue from the vessels and then subjects them to a battery of high-tech tests to see what our ancestors drank in their day. His books, “Uncorking the Past: The Quest for Wine, Beer and Other Alcoholic Beverages,” and “Ancient Wine: The Search for the Origins of Viniculture,” have chronicled his work.

In more than 20 years in the field, McGovern has made several important and startling discoveries. He’s identified the world’s oldest known barley beer (dating to 3400 B.C. from Iran’s Zagros Mountains), the oldest grape wine (from 5400 B.C., also from Zagros), and the earliest known alcoholic beverage of any kind, a Neolithic concoction some 9,000 years old, from China’s Yellow River Valley.

His latest published work focused on the chemical fingerprint that pinpointed the origins of winemaking in France. His research showed that imported ancient Etruscan amphoras and a limestone press platform, discovered at the ancient port site of Lattara in southern France, held the earliest known biomolecular archaeological evidence of grape wine and wine making in France. The find points to the beginnings of Celtic vinicultural industry in France some 2,500 years ago.

And where did it come from? Apparently, it was imported from Italy. McGovern is the lead author of “Beginning of Viniculture in France,” which details this find in the June 3, 2024 issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Confirmation of the earliest evidence of viniculture in France as actually coming from Italy (it had been widely suspected) is a key step in understanding the ongoing development of what McGovern calls the “wine culture” of the world – one that began in Turkey’s Taurus Mountains, the Caucasus Mountains and/or the Zagros Mountains of Iran about 9,000 years ago.

“France’s rise to world prominence in the wine culture has been well documented, especially since the 12th century, when Cistercian monks determined by trial and error that Chardonnay and Pinot Noir were the best cultivars to grow in Burgundy,” McGovern said. “What we haven’t had is clear chemical evidence, combined with botanical and archaeological data, showing how wine was introduced into France and initiated a native industry.”

The Lattara site, merchant quarters inside a walled settlement (circa 525-475 B.C.), held numerous Etruscan amphoras, basically narrow necked jars, three of which were selected for analysis because they were whole, unwashed (a key point), found in an undisturbed sealed context and showed sign of reside on their interior bases where precipitates of liquids, such as wine, collect. Judging by their shape and other features, McGovern said, they could be assigned to a specific Etruscan amphora type, likely manufactured at the city of Cisra (modern Cerveteri) in central Italy during the same time period.

Armed with advanced chemical analysis instrumentation McGovern aims his attention to the precipitates from the ancient jars.

After sample extraction of any where from 1 to 100 mg, the ancient organic compounds were identified with a combination of analysis techniques, including infrared spectrometry, gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, solid phase microextraction, ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry and a technique which was being used for the first time to analyze ancient wine and grape samples, liquid chromatography-Orbitrap mass spectrometry.

“Orbitrap is the most sensitive” technique used, McGovern says, “but the other techniques provide good information as well.”

All the samples were positive for tartaric acid/tartrate (the biomarker for the Eurasian grape and wine in the Middle East and Mediterranean), as well as compounds derived from pine tree resin. Herbal additives to the wine were also identified, including rosemary, basil and/or thyme, which are native to central Italy where the wine was likely made. (Alcoholic beverages, in which resinous and herbal compounds are more easily put into solution, were the principle medications of antiquity.)

Nearby, an ancient pressing platform, made of limestone and dated circa 425 B.C., was discovered. Its function had previously been uncertain. Tartaric acid/tartrate was detected in the limestone, demonstrating that the installation was indeed a winepress. Masses of several thousand domesticated grape seeds, pedicels, and even skin, excavated from an earlier context near the press, further attest to its use for crushing transplanted, domesticated grapes and local wine production.

This, for McGovern, was the clincher that the press was used in wine making and not olive pressing. Olives were extremely rare in the archaeobotanical corpus at Lattara until Roman times. This is the first clear evidence of winemaking on French soil.

“Since French cultivars are now the exemplar of fine winemaking and their cultivars planted world-wide, the introduction of the grapevine there and the beginning of winemaking there is very important,” McGovern explains.

“Where wine went, so other cultural elements eventually followed,” McGovern adds, “including technologies of all kinds and social and religious customs—even where another fermented beverage made from different natural products had long held sway.”