New Bird-like Dinosaur is Clue to Evolutionary Experimentation

A strange new bat/bird dinosaur fossil has been found, according to a new Nature study. Its skeleton indicates the creature was a pioneering flyer whose bones were unlike prehistory’s most primitive birds.

A strange new bat/bird dinosaur fossil has been found, according to a new Nature study. Its skeleton indicates the creature was a pioneering flyer whose bones were unlike prehistory’s most primitive birds.

It is an example of, if nothing else, the extraordinary evolutionary experimentation that occurred in the Jurassic era, when birds were forming.

“The specimen is quite surprising in the presence of the bony rod and the elongation of the lateral finger of the hand,” Fort Hays State University Associate Curator of Vertebrate palaeontologist Christopher Bennett, Ph.D., told Bioscience Technology. Bennett was uninvolved with the study. “It shows that lots of animals were trying lots of different things to get into the air or to get down from heights.”

First author Xu Xing, a palaeontologist with Beijing’s Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Ph.D., told Bioscience Technology that “when I saw the rod-like bones near the wrist, I got really confused and surprised. Major evolution transitions are more complex than we thought, including the transition to birds.”

Jurassic rocks

The new fossil, found in Jurassic rocks in northeast China’s Hebei Province, appeared to be the remains of a creature that possessed wings made of skin, not feathers, according to the research, which was conducted by the team of Xu, and second author author Zheng Xiaoting of Linyi University in Shandong Province.

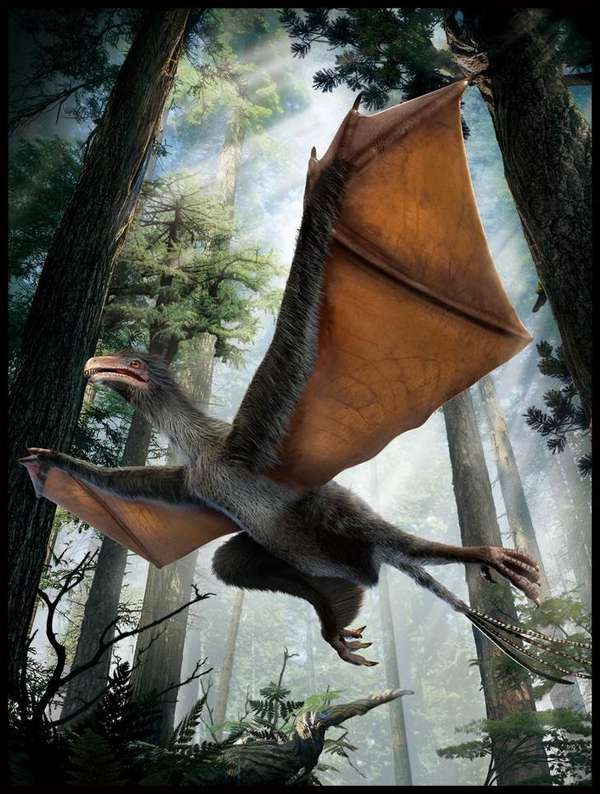

The team named their bird Yi qi, translated as “strange wing” in Mandarin, as it apparently resembled that of a bat, or flying squirrel, more than a standard bird.

Yi qi is a member of a China-only group of dinosaurs referred to as scansoriopterygids, which are cousins of birds like Archaeopteryx, transitional flightless creatures falling somewhere between feathered dinosaurs and modern birds.

Yi qi initially seemed flightless, too. Feathers were found at the site, but they appeared unsuitable for the formation of flight surfaces. At length, the crew recognized that the fossil’s long, rod-like bone, which extended from each wrist, was evidence of a very different kind of wing.

Bats and flying squirrels have similar rods of bone or cartilage that work in conjunction with limb joints. The rods bolster the wings’ aerodynamic membranes. And indeed, the China team also discovered membranous tissues, if the shape and size of the membrane they formed has remained unknown.

Bats and flying squirrels have similar rods of bone or cartilage that work in conjunction with limb joints. The rods bolster the wings’ aerodynamic membranes. And indeed, the China team also discovered membranous tissues, if the shape and size of the membrane they formed has remained unknown.

This kind of flight apparatus has never been associated with dinosaurs.

“Although my first instinct was to try to interpret the bony rod as anything but a new bony structure projecting from the wrist, I do not think that I can,” Bennett told Bioscience Technology. “I am surprised that the bony rod seems to be more robust that the forearm bones, i.e., the radius and ulna. But that may be a function of its length. I am also surprised because it seems that Yi had evolved something like a bat wing, though I agree with the authors that it seems likely that the animal was a glider rather than an active flier.”

In the future, Bennett said, he hopes the team finds additional specimens “that will shed light on the unusual evolutionary direction that Yi was going. But it does seem at present that it was an evolutionary dead end rather than an important step in the path to living birds… I look forward to new finds.”

Cautioned Xu: “There are many unusual things in evolutionary history that we probably will never get chance to find.”