We Gain 20,000 Species Yearly—But Lose More Than That

We are discovering 20,000 new species per year, says Quentin Wheeler, Ph.D., president of the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry (ESF).

We are discovering 20,000 new species per year, says Quentin Wheeler, Ph.D., president of the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry (ESF).

But we are also losing 20,000-plus species a year due to extinction, he says.

So his team annually publicly celebrates the discovery of 10 of the most interesting newly discovered species, to bring attention to the fact that, if humans don’t take far greater care of them all, we may have a mass extinction of 70% of all species on Earth within 300 years.

Conservative estimators say that “we are losing species at about the same rate at which we are discovering species, perhaps 20,000 species per year,” Wheeler told Bioscience Technology. Reasons for the losses range from climate change to pollution to over-development--and beyond.

Indeed: “Others, including many experienced tropical biologists, would tell you the loss rate is twice that or more. That means 50 to 100 species per day. One recent study projected that, at the current extinction rate, that we will officially witness a mass extinction--the loss of 70% or more of all species--within just 300 years. Such speed for entering a mass extinction is unprecedented in earth history.”

“Amazing, morbid, and cool”

The list is compiled annually by ESF's International Institute for Species Exploration (IISE). The institute's international committee of taxonomists selected the Top 10 from among the approximately 18,000 new species named during the previous year. ESF released this year's list May 21 to recognize the birthday, May 23, of Carolus Linnaeus, an 18th century Swedish botanist who is considered the father of modern taxonomy.

This year’s list of newcomers is diverse, consisting of “newly discovered species including animals, plants, and microbes,” Wheeler told Bioscience Technology. “One of my favorites—how can you have just one?—is the boneyard wasp [or Deuteragenia ossarium, from China]. As the character Ian Malcolm says in the movie “Jurassic Park”: `Life finds a way.’ The boneyard wasp’s use of ant corpses to create a chemical curtain at the front door of her nest to secure her developing larvae is morbid, amazing and cool in equal measure.”

The candidate this year offering the most precautionary message is the Coral Plant, or the Balanophora coralliformis, Wheeler said. Found in the Philippines, this long-branched parasitic coral-like tuber plant numbers in the 50’s. Shortly after its discovery, it may disappear. “With just 50 individuals in a small unprotected area it is likely not long for this earth,” he told Bioscience Technology.

Read More: Genetics Allow Animals to Produce their Own Sunscreen

The most useful species—to humans—in the Top Ten is the cartwheeling spider, or Cebrennus rechenbergi. Because it lives in Moroccan deserts with few places to hide, it apparently believes it has little choice but to cartwheel –which it can do far faster than it can run—straight at predators to frighten them away.

Scientists have already studied the mechanics of these and employed them in a biomimetic robot that can walk or roll in a similar way.

Amazing world

“I believe that the lists have reminded people what an amazing world we live in, how little we know of its precious inhabitants, and why we should be alarmed that the biodiversity crisis is wiping out species before they are even known,” Wheeler told Bioscience Technology. “I hope, too, that it is a reminder of the excitement of basic taxonomy, field natural history, and of natural history museums. We do not have hard data on impact, but interest in the Top 10 remains very strong and people clearly are fascinated by discovery.”

The lists are drawing attention to new species, but are not yet resulting in dramatic numbers of new policies and hires.

“While public awareness of these issues is the motivation for the list, I am disappointed that trends in hiring and funding have not changed—yet, I am an optimist—within the science community. The average rate of discovery of 18,000 species per year is unchanged since the 1940s in spite of technological advances. It is critically important that we learn more about the evolutionary novelties of each species than a DNA  barcode that, while very useful, reduces the amazing story of each species to a single dimension. The biodiversity crisis makes this work urgent, but calls for a worldwide inventory of life have not yet been answered by funding and serious action.”

barcode that, while very useful, reduces the amazing story of each species to a single dimension. The biodiversity crisis makes this work urgent, but calls for a worldwide inventory of life have not yet been answered by funding and serious action.”

Wheeler’s personal loss

Wheeler believes one of the lost species may be one of his own.

“One of my former students, Joe McHugh, now a professor at the University of Georgia, and I described a beautiful, graceful little beetle we named Dasycerus maculatus from the mountaintop spruce-fir forests in the southern Appalachian mountains. The woolly adelgid, and air pollution, hit the fir trees hard, and the status of our new species is unknown. I hope it is not extinct, but its range is very restricted and it is clearly vulnerable to these unique high-elevation forests.

A living fossil; an artiste fish

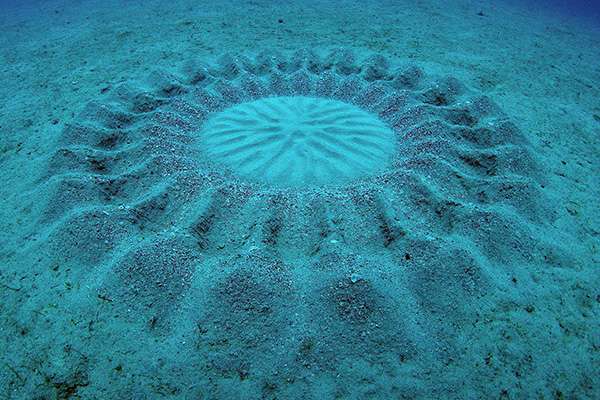

The other 2015 winners include: a feathered dinosaur fossil—or what the Wheeler team has dubbed 'Chicken from Hell'—called Anzu wyliei, found in the US; a strange mushroom-like (yet jellyfish-type) creature from Australia called Dendrogramma enigmatica that is alive, but resembles fossils from the Precambrian, perhaps making it a living fossil; and a pufferfish called Torquigener albomaculosus, found in Japan, which creates art on the bottom sea floor. By wriggling in a calculated fashion, it forms intricate, geometric patterns of rings.

Males build these circles as spawning nests to attract females. The ridges and grooves of the circles minimize currents, protecting the eggs from both rough seas, and predators.

_itok-4tfCXO71.jpg)