Historic Japan Stem Cell Trial Approved

The first clinical trial of revolutionary stem cells that won a Nobel Prize for their developer has been greenlit.

The first clinical trial of revolutionary stem cells that won a Nobel Prize for their developer has been greenlit.

The cells, called induced pluripotent stem (iPS) Cells, will be morphed into retinal cells, then given to six patients with a major cause of blindness: age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

The trial, approved by Japan Health Minister Norihisa Tamura, will be led next summer by Masayo Takahashi. She is a retina regeneration expert, and a colleague of the man who first developed iPS cells: Shinya Yamanaka.

The trial epitomizes, to many, Japan’s determination to dominate the iPS cell field, an ambition that kicked into high gear when Yamanaka shared the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine last October for his iPS cell work.

“If things continue this way, this will be the first in-clinic study in iPS cell technology,” says Doug Sipp of the Riken Center for Developmental Biology (CDB). The CDB, Takahashi’s institute, will co-run the trial with Kobe’s Institute for Biomedical Research and Innovation. "It's exciting."

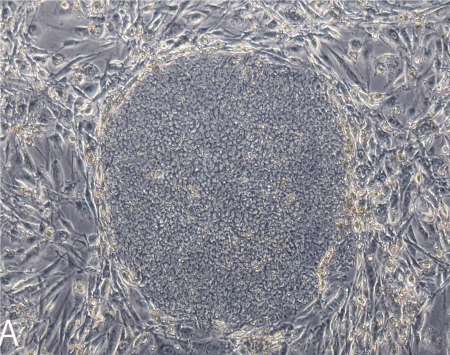

Sipp notes the move surprises few in Japan, which is investing heavily in iPS cells. Still, Takahashi has not formally published the details of her trial, which is raising some eyebrows. IPS cells are hailed as the perfect compromise cell. They are adult, so uncontroversial; multi-potent like an embryonic cell, so relatively powerful.

Sipp notes the move surprises few in Japan, which is investing heavily in iPS cells. Still, Takahashi has not formally published the details of her trial, which is raising some eyebrows. IPS cells are hailed as the perfect compromise cell. They are adult, so uncontroversial; multi-potent like an embryonic cell, so relatively powerful.

But they were only created in 2007; remain difficult to create and culture; and can go tumorous in many hands, many note.

Others like Sipp note, however, that Riken’s CDB alone has produced world-class work with all kinds of stem cells, including embryonic stem (ES) cells, the models for iPS cells.

Indeed, Sipp and others note, it is widely acknowledged that Takahashi’s sometime collaborator, Riken’s Yoshiki Sasai, is doing groundbreaking work with ES cells and the eye. Nature has called him “The Brainmaker,” and has said his research is “wowing” the world.

The trial is certainly supported. The health ministry’s recent stimulus plan earmarks more for stem cells—particularly iPS cells—then anything else: 21.4 billion yen ($215 million), according to Nature. Of that, the health ministry set aside 700 million yen ($7 million) for a cell-processing center to support Takahashi—before her trial was even approved. Two centers devoted to iPS cells will be built with 2.2 billion yen ($22 million). The AFP reports the prime minister has set aside a breathtaking $1.18 billion, all told, for iPS-cell work. Yamanaka told Nature the government seems to be “telling us to rush iPS cell-related technologies to patients as quickly as possible.”

Indeed, Robert Lanza, CSO of Advanced Cell Technology, might once have been the logical bet to be first to the clinic with iPS cells. Unlike Takahashi, he has three ES cell trials under his belt, and has started talks with the FDA about transplanting iPS cell-derived platelets.

But his iPS proposal is taking longer.

In the US, he notes wryly: “We don’t have the prime minister and emperor to speed things along for us.”

Japan has focused on iPS cells since 2007, the year Yamanaka reported that tweaking four genes could change limited adult human cells into potent, embryonic-like cells. “At Yamanaka’s institute alone, there are at least 20 teams focusing on iPS cells now,” Sipp says. (The Center for IPS Cell Research and Application was created expressly for Yamanaka.) There are teams at Riken, the Universities of Tokyo and Keio, and others. “A lot is happening here.”

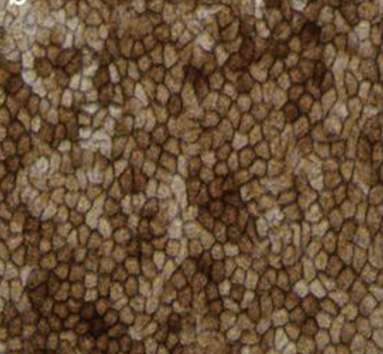

Takahashi has reported part of her plan to scientific meetings. She told the International Society for Stem Cell Research in June 2012 she had created iPS-cell derived retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells for transplant. RPE cells nourish the photoreceptors that often die in blindness. She reported her RPEs possess proper structure and gene expression; do not go tumorous in mice; survive six months in monkeys. Vision was not tested. But she noted some AMD patients’ sight improves when RPE cells are moved from the eye’s periphery to its center.

Takahashi has reported part of her plan to scientific meetings. She told the International Society for Stem Cell Research in June 2012 she had created iPS-cell derived retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells for transplant. RPE cells nourish the photoreceptors that often die in blindness. She reported her RPEs possess proper structure and gene expression; do not go tumorous in mice; survive six months in monkeys. Vision was not tested. But she noted some AMD patients’ sight improves when RPE cells are moved from the eye’s periphery to its center.

She has published many iPS and ES cell papers, two with Yamanaka: one on creating retinal cells from iPS cells, and one on creating safe iPS cells. She has not published trial details. It is not required. But such a landmark trial should be transparent, many stem cell experts argue.

Still, she has submitted a relevant paper to a top journal for review, Sipp says, adding that this is purely a safety trial (called a “clinical study” in Japan). And Lanza has reported in The Lancet that similar, if small, trials are doing well. His three ES cell trials treat Stargardt’s macular dystrophy and AMD (if his treats “dry,” while hers would treat “wet” AMD). The replaced cells are also RPE cells. This is good news for her.

Paul Knoepfler, a high profile stem-cell expert, has noted in his well-read industry blog that the ministry overseeing Takahashi’s trial will reportedly monitor some key factors: gene sequencing and tumorigenicity. But he is also calling for more details.

The Japanese Health Ministry and the US FDA recently agreed to devise a joint regulatory framework for retinal iPS cell clinical trials, to go live by 2015. Takahashi’s trial is set for 2014.